150 years of the F.A. Cup - how the first competition shaped today's global game

By Mark Gorton 14th May 2022

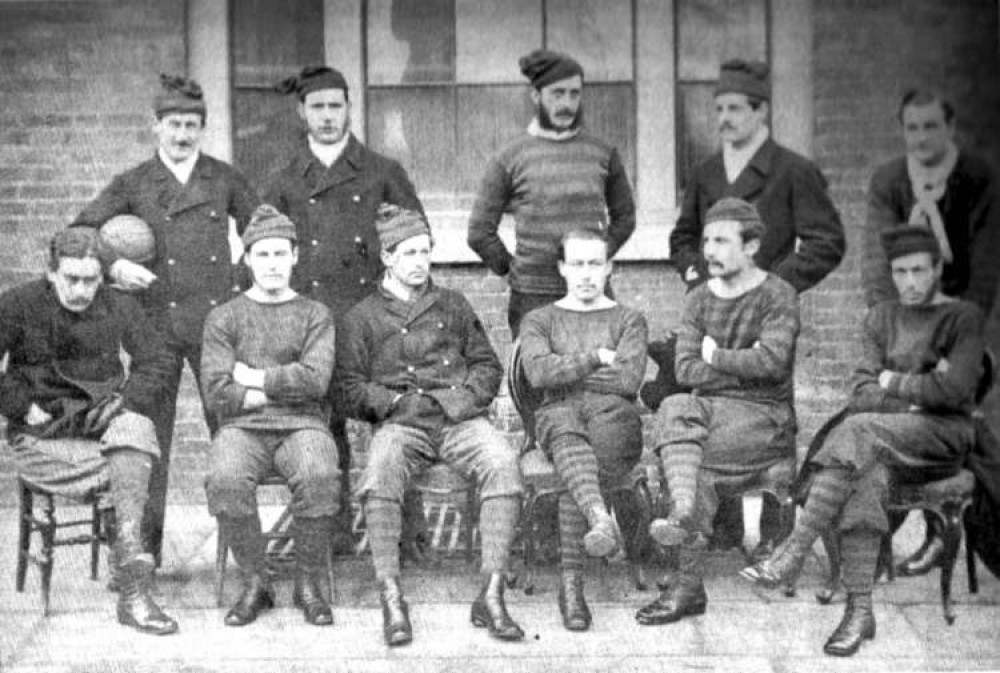

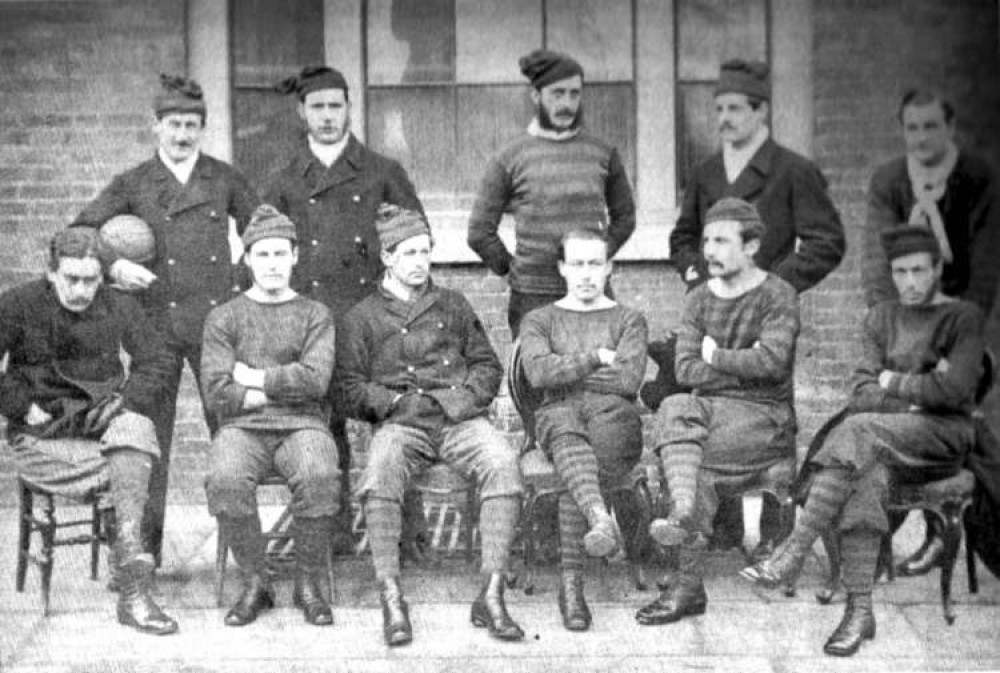

Above: Royal Engineers - runners-up in the first F. A. Cup Final, 1872

In 1871, 29 year-old keen footballer and captain of a team called the Wanderers, Charles W. Alcock, came up with an idea to promote the game he loved - a nationwide knock-out competition modelled on the inter-house sporting contests he had enjoyed at Harrow School.

The 'hard working centre forward with an accurate shot', also described as 'a man of fine and commanding presence who had a happy knack of persuading people to his way', summoned representatives of seven other clubs to the offices of The Sportsman periodical and described his vision of football reaching beyond the public schools.

Back then, football was dominated and controlled by the amateur elite. Charles did not realise he was sowing the seeds of professionalism that, just 11 years later, would ultimately cause the demise of the game with which he was familiar.

Alcock's plan was approved and teams from all parts of Britain were invited to take part. A demand for a guinea from each to pay for the fashioning of the Challenge Cup put some off, while others were daunted by the prospect of travelling to a tournament held solely in London.

15 clubs did enter, however, though logistics teething problems meant that Scottish side Queen's Park progressed to the semi-final without actually playing a game. In that semi the Scots squared up against Wanderers and the result was nil-nil.

Royal Engineers' match against Crystal Palace was also goalless, but they booked their place in the final by winning the replay 3-0.

Meanwhile, Queen's Park decided they could not be bothered making another costly trip south and withdrew from the competition, meaning the Wanderers wandered unopposed into the final.

2000 spectators watched the game at cricket's Kennington Oval, though Alcock's attempts to popularise the event were undermined by the cost of a ticket, which was one shilling. The crowd was described in the press as 'fashionable and well to do', regarding the game as both a social occasion and sporting event. In contemporary terms, it seems the atmosphere was more Royal Ascot than Wembley.

But the game did not disappoint. The Field reported: "It was the fastest and hardest match that has ever been seen at The Oval. Some of the best play on the Wanderers' part, individually and collectively, was the finest ever shown in an Association game."

Singled out for particular praise was Robert Walpole Sealy Vidal, 'the prince of the dribblers', whose zig-zagging run and pass enabled Morton Peto Betts to become the first man to score an F. A. Cup goal.

Final score: Wanderers 1, Royal Engineers 0.

In 1872 the rules of football were still being formed. Charles Alcock had made a stab at standardisation with his book, The Rules of Foot Ball, but games were often punctuated by disagreements over what was legal and what was not, and, on several occasions, had to be abandoned.

The referee was still in the future. Instead, players had to appeal for a goal to an umpire who stood outside the field of play. After a goal, teams changed ends and the scoring side had the kick-off - which, it is said, once allowed Walpole Sealy Vidal to score three times without the opposition touching the ball.

For goals, a tape was stretched between two poles eight feet high; throw-ins were taken one handed and decided not by who touched the ball last, but who got to the out of play ball first; and hacking at your opponents' shins was actively encouraged and not a straight red card.

Historian Professor Tony Collins has described the Pandora's box opened by the first F. A. Cup like this: 'During the late Victorian era the Cup was an unprecedented social leveller as working class teams from industrial towns decided to enter – you would get blokes from the local factory kicking the living daylights out of peers of the realm. Unsurprisingly, this became an increasingly popular spectator sport.'

The public schools' domination of football ended in 1883 when Blackburn Olympic, not even the best team in the town, also home to the superior Rovers, won the F. A. Cup at The Oval by beating Old Etonians 2-1 after extra time.

But Olympic didn't kick their opponents into submission. Far from it, because the Blackburn boys had mastered the combination game, which we now know as passing the ball. The Old Etonians' preference for scrimmaging and dribbling, with six forwards playing up front, couldn't cope.

What's more, the Olympic players were trained by a great defender called Jack Hunter, who had been made landlord of a Blackburn boozer - an early form of transfer fee and highly questionable at the time - to persuade him to join Olympic from Sheffield Zulus.

The amateur game had begun to give way to professionalism.

Football would never be the same again.

CHECK OUT OUR Jobs Section HERE!

heswall vacancies updated hourly!

Click here to see more: heswall jobs

Share: