Books: how two of America’s greatest writers spent time in Liverpool and Southport 166 years ago (and one of them, briefly, in Wirral)

By Mark Gorton 22nd Nov 2022

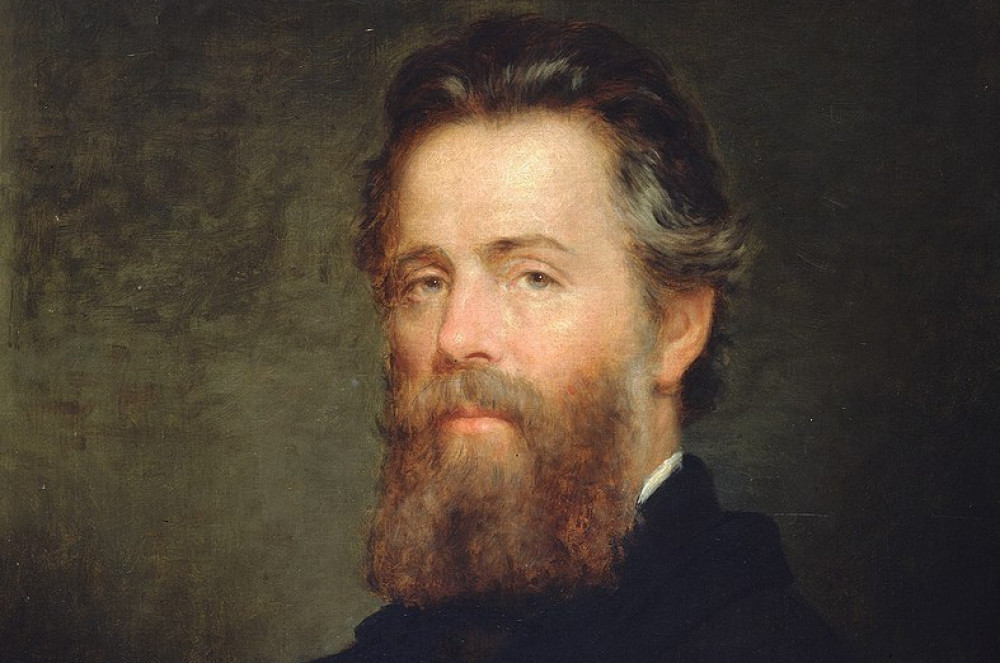

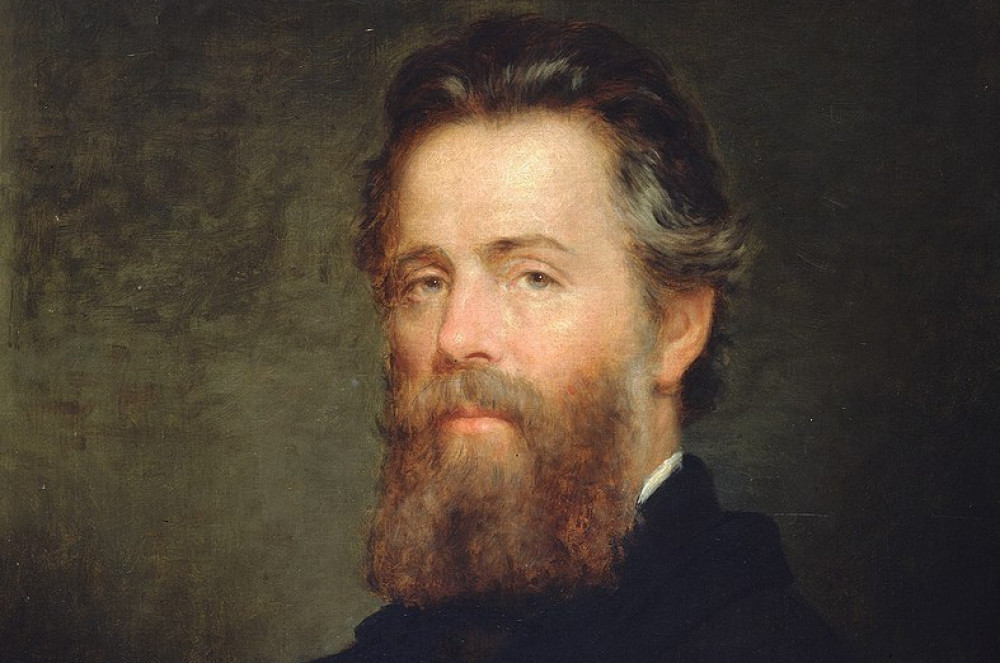

Herman Melville, creator of Captain Ahab's obsessive hunt for the white whale, Moby Dick, was slave to a self-destructive quest of his own. An outsider, possessed by a hectic and confused interior life, Melville had long hovered between belief and doubt, faith and cynicism, light and darkness.

But by the early 1850s a malign and persistent shadow had fallen across him: at worst the universe was a conspiracy to inflict suffering; at best it was a vast practical joke. His well-being, both physical and spiritual, began to decline. He was pale and distracted and endured headaches and pain.

In 1856 Melville made an escape bid from his troubled self. He left New York on board a screw steamer bound for Glasgow with the aim of visiting Europe and the Holy Land. "I stayed in Glasgow three or four days," he recorded in his journal. "From Glasgow I went to Edinburgh, remaining there five days I think. From Edinburgh I finally went to York. After a day's stay to view the Minster, I came here."

Here was Liverpool in early November. Melville arrived just after midday on Saturday the 8th. He took a room in the White Bear hotel and then re-traced some of the steps he had taken during his first visit when, aged 20, he had sailed to the port as a boy on a packet. He was planning to sail from Liverpool to Constantinople, but also take the opportunity to look up his old friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Hawthorne, like Melville, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman, was a bright bloom in the first great flowering of American literature. Best known for The Scarlet Letter he was now American Consul at Liverpool and had made a home for his wife and children in Southport.

At first they had been based in Rock Ferry, and Melville crossed the Mersey and went there only to be disappointed.

The two men were first reunited at the Consulate and, although friends, their initial exchanges were uncomfortable. Hawthorne had tried without success to secure a consular appointment for Melville and was embarrassed by his failure. And Melville was simply Melville, "looking much as he used to," wrote Hawthorne later, "a little paler and perhaps a little sadder, in a rough outside coat, and with his characteristic gravity and reserve of manner.

The discomfort ebbed away and we soon found ourselves on pretty much our former terms of sociability and confidence." Melville described the journey he was making and they talked of the home he had left behind. Hawthorne doubtless looked closely at his friend. He knew at once that his health was poor and had "long believed that his writings have indicated a morbid state of mind."

Hawthorne invited Melville to stay in his Southport home for as long as he might remain in the vicinity. Melville accepted and arrived there the next day having picked up his luggage from his hotel. The paucity of his belongings shocked Hawthorne: "The least bit of a bundle, which contained a night-shirt and a tooth-brush. He is a person of very gentlemanly instincts in every respect, save that he is a little heterodox in the matter of clean linen." Hawthorne did not understand that Melville was a sailor at heart; he could live rough and travel light.

Melville stayed with the Hawthornes from Tuesday to Thursday. Here there were roaring fires, hearty meals and the simple pleasure of conversation with Hawthorne's children, Julian and Una. But although Melville brightened that first night in Southport the mood did not last.

On the Wednesday the two writers took a walk along the strand. There was a cold wind blowing across the deserted sands, a landscape that seemingly matched or encouraged Melville's troubled spirits. In America and in happier times the two men had talked at great length, Melville noting that Hawthorne's ability to listen in thoughtful silence was a unique quality. But now, as the desolate wind blew, Melville simply wanted desperately to unburden himself and Hawthorne was troubled by what he heard.

Melville described territory he had spoken of before, only now he seemed hopelessly lost there.

"We sat down in a hollow among the sand hills," recalled Hawthorne, "sheltering ourselves from the high, cool wind and smoked a cigar. Melville began to reason of Providence and futurity, and of everything that lies beyond human ken, and informed me that he had pretty much made up his mind to be annihilated, but still he does not seem to rest in that anticipation; and, I think, will never rest until he gets hold of a definite belief. It is strange how he persists in wandering to-and-fro over these deserts, as dismal and monotonous as the sand hills amid which we were sitting."

The gulls echoed Melville's loneliness and the lights of little lives shone from the town's windows. Finally the cold and the gathering darkness ended an endless conversation. The two men, saddened and silent, returned home.

The next day Hawthorne had business back in Liverpool. Melville went sight-seeing in the city and made enquiries about passage among the steamers. On Saturday the friends took a day trip to Chester, but if Hawthorne had hoped to cheer up Melville it was in vain. They parted on a Liverpool street corner, Melville turning away into the night and the rain.

They met for the last time on Monday. Melville, for his friend's sake, said he felt much better than in America. But Hawthorne noted: "He certainly is much overshadowed but I hope he will brighten as he goes onward."

He did not. When Melville sailed from Liverpool he was once again in flight across a sea as vast and lonely as his own imagination; and once again in pursuit of the fabulous but terrifying submarine creatures that cruised through his psyche.

If you'd like to read "Moby Dick "and, say, Hawthorne's "The Scarlet Letter", of course we are lucky to have independent bookseller Linghams on Telegraph Road.

CHECK OUT OUR Jobs Section HERE!

heswall vacancies updated hourly!

Click here to see more: heswall jobs

Share: